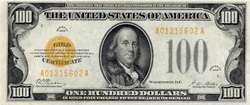

Up until that time, the 1920’s was unlike any other decade in the history of the United States. The newly formed Federal Reserve Bank was exerting some form of stability on the more than 25,000 banks in the United States, and because of technology, the car and housing industry were expanding (many homes were getting both electrified and internal plumbing) and the stock market was booming, in part because of buying on the margin. We were also on the gold standard. In other words, even though there was an abundance of paper money, many of these, gold certificates, could be redeemed for gold, generally $1-$50 gold pieces.

When buying a stock on the margin, your stockbroker lends you money, and then charges you interest plus the commission on the sale. During the 1920’s, the margin rate was 90% (it’s currently 50% and is determined by the FED). In other words, you would be able to buy $1000 worth of stock while only putting up $100. For instance, if you want to buy 100 shares of General Electric (the only stock that has been on the Dow Jones Industrial Average since its inception in 1896), that was selling for $10, you would give your broker $100 and he would lend you the other $900. In an up market, this is great. If the stock increases to $15 and you sell, you pay your broker back and receive $500 on your $100 investment (less interest and commissions). But what happens if the stock decreases to $5? The broker has what’s known as a margin call. Essentially, he wants his money. At that time everyone was in the market because of the high margin rate including blue collar workers. These people didn’t have the money, so they are out there $100, the broker is out their money, and since many brokerage houses were banks or borrowed from banks, the banks were out their money. At the time there was no FDIC and your money in the bank wasn’t insured. As a result, it wasn’t long before word got out and there was then an immediate run on the banks.

Glass-Steagall and the FDIC restored immediate confidence in the banking system, and as a result, there were less than 65 bank failures in 1934. For the rest of the decade, the economy made a slow recovery and by 1941, the unemployment rate was 10.1%. However, within 2 years the unemployment rate was down to 1.7% as a result of the government spending vast amounts of money (48% of GDP) as a result of WW II.

Two afterthoughts:

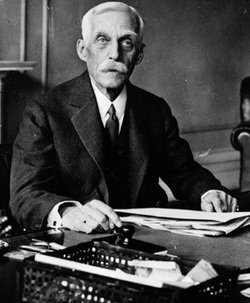

In 1932, Congress began impeachment proceedings of Andrew Mellon; however he resigned and was given an Ambassadorship position.

There are times when we do learn from history. During the financial crisis of 2008 and subsequent recession, then FED Chairman Ben Bernanke (a true scholar of the depression), injected huge amounts of liquidity into the banking system greatly increasing reserves and the FED balance sheet which increased from $800 billion to over $4 trillion, thus avoiding what could conceivably have been a 2nd depression in 100 years. I firmly believe that history will be very kind to Chairman Bernanke.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed